Evaluating the influence of old and new rental systems on the physical condition of historic mixed-use buildings: a case study of Lebanon

- Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering, University of Applied Science, Manama, Bahrain

This article investigates the link between the physical condition of built heritage and official local authorities’ legislation in Lebanon. The research analyzed the impact of occupation on the physical condition of dwellings under the prevailing official inherited rental legislation, identifying the scale of the problem and the factors leading to it. The responsibilities of the Lebanese official bodies for rental legislation regarding historical buildings were thoroughly discussed. Moreover, a field survey for the condition of historical dwellings was conducted. To accomplish its objectives, the study employed a three-stage methodology. The first stage involved reviewing archival records, current legislation, and relevant literature to gain a comprehensive understanding of historical dwellings laws and regulations in Lebanon. The second stage was divided into two parts. First, the case study area of the Yacob Al Labban historical square in Tripoli, Lebanon, was selected and justified. This area was examined to understand the impact of local authorities’ legislation and rental regulations on the physical condition of its historical dwellings. Second, a field survey was conducted to gather specific information on building typology, physical condition, and building defects. This data will help establish a connection between legislation and buildings’ physical conditions. In the third stage, the findings were analyzed, interpreted, and compared with the existing literature to draw meaningful conclusions about the relationship between legislation and the condition of historical buildings in Lebanon. The research results revealed a strong relationship between the deterioration of historical dwellings and rental legislation. Additionally, the study found that low rental fees were directly associated with a lack of maintenance across all types of rentals.

1 Introduction

Historical buildings possess a unique allure, attracting tourists and serving as architectural landmarks within specific territories (Scerri, M., Edwards, D., & Foley, C., 2016). However, in developing countries such as Lebanon, the preservation of historic urban fabrics faces a complex and multi-dimensional dilemma (El-Bastawissi et al., 2022). Decision-makers and local stakeholders often struggle to recognize the benefits of conserving built heritage, particularly when attempting to adapt these structures to contemporary living spaces (Diaz et al., 2015; Afify, 2014). Compounding this challenge are rental legislations that fail to align with urban conservation requirements (Peppercorn, I. G., & Taffin, C., 2013).

Maintaining a delicate balance between conservation and redevelopment proves challenging, particularly in developing countries (Al-hagla, 2010; Sadi et al., 2013; Elnabawi et al., 2022). The question arises: should historical buildings be frozen in time, resembling museum artifacts, or should they be integrated into a modern, economically thriving environment (Bianca, 2000)? To achieve successful conservation projects, decision-makers must prioritize local problems and traditions over global and Western concepts, understanding that the objective is not merely to transform historical areas into tourist zones (Laraichi, 1981; Salam, 1998; Sandes, 2013). The protection of historic center monuments and beautiful buildings alone is insufficient; safeguarding the wider region in which they reside is equally crucial (Sitte, 1986). In many cases, the preservation of a historic urban fabric aims to renew, enhance, and integrate the old historic environment into a new, thriving context (Amiot, C. E. et al., 2007; Jin, S. et al., 2022).

Governments play a vital role in encouraging conservation, restoration, and rehabilitation processes. By implementing policies and measures to stimulate private sector investment in architectural heritage, they can provide the necessary economic justification for preservation (Wojno, C. T., 1991; Elnabawi et al., 2022). However, in Islamic countries such as Lebanon, inheritance regulations introduce additional complexities, often resulting in endless divisions and disputes over properties, including dwellings and other building types (Skaist, 1975). These disputes can lead to neglect, deterioration, and compromised structural integrity when multiple heirs fail to reach a consensus on maintenance and investment decisions (Smith & Johnson, 2018; Brown & Wilson, 2019; Elnabawi et al., 2022).

The challenges extend to the rental agreement realm, particularly within the studied urban fabric of historical buildings in Lebanon (Gerston, 2014). Historical edifices require specialized preservation processes while limiting the options for functional adaptations within their structures. This raises complex questions regarding the responsibilities outlined in the current rental legislation and poses challenges in finding suitable solutions (Gerston, 2014).

To address these issues, it is crucial to establish clear chapters in the legislative framework that define the responsibilities of each party involved in the preservation and maintenance of historical buildings. Additionally, a quantitative research analysis is necessary to understand the impact of rental legislation and propose effective methods for managing historical dwellings. This research aims to bridge the gap between legislation and the physical condition of historical buildings, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of their preservation in Lebanon.

2 Methodology

This study is a case study research based on the following three-stage methodology:

Stage 1: Reviewing archival records and relevant literature. In this stage, the current legislation regarding rental, maintenance, and historical building regulations in Lebanon was reviewed. Furthermore, relevant articles, journals, and books with the same focus were reviewed. The purpose was to gather information and gain a comprehensive understanding of historical dwellings laws and regulations in Lebanon.

Stage 2: This stage consisted of two main parts. In the first part, a case study was selected and justified. Yacob Al Labban historical square in Tripoli, Lebanon, was chosen as the case study area to examine and illustrate the findings related to the impact of the local authorities’ legislation and rental regulations on the physical condition of its historical dwellings.

In the second part, a field survey was conducted to gather specific information. The survey aimed to identify the building occupancy pattern, distinguishing between non-residential and residential use, and any monetary implications. Additionally, it aimed to assess the physical state of the buildings and identify any major defects.

By conducting this field survey, the research aimed to gather and analyze comprehensive data on building typology, physical condition, and major defects of the historical buildings in the case study area. This data would contribute to a deeper understanding of the relationship between legislation and building typology and physical conditions.

Stage 3: Presenting and discussing the results of the study. This includes the findings related to the correlation between the physical condition of historical dwellings and official local authorities’ legislation and the effect of occupation on their physical condition under the prevailing rental legislation. The results have been analyzed, interpreted, and compared with the existing literature to draw conclusion and insights regarding the relationship between legislation and the condition of historical buildings in Lebanon.

3 Current legislation

Most cities are full of underutilized historic buildings (Isabel Morris, 2017). A lot of the world’s historic buildings and sites are protected by legislation and active conservation organizations, which understand the invaluable historical essence of such places. For example, ‘reasonable standards of health and safety’ specify that when work is being carried out to a historic building, it should not result in a less safe environment (John Adams, 1997).

Essentially, the Construction Law (Law No. 646 of 2004) in Lebanon regulates the appearance and structural integrity of buildings. The Municipal Law (Decree/Law No. 118 of 1977) gives municipalities the responsibility of ordering owners to rehabilitate and restore buildings at their expense and controlling infringement on regulations. Additionally, the Rental Law (the “Old” 1945 Rent Law and Rent Acts No. 159 and 160) in 1992 allows periodic revisions of rents.

3.1 Rental legislation in Lebanon

Lebanese renting laws are in continuous change. Following Lebanon’s independence in 1943, there was a single renting format known as the old law; contracts used to be done upon a mutual agreement without a prior official pricing. All contracts used to be automatically extended each year, and the tenant acquired a higher sense of safety and belonging to the place. In that era, renting contracts assigned various obligations on the owner’s side, such as electricity and utility bills, not to mention all the required maintenance (Rafferty, 2022). However, renting rates were profitable to landlords at that time, and many of them launched construction projects aiming to construct new buildings dedicated for rentals. However, the “everlasting” renting agreements were finely agreed due to the economic prosperity. The economic decline during the civil war (1975–1990) and post-war socio-economic changes modified the formula due to the great decline of the national currency. The owners ceased to perform maintenance and related services, and tenants refused to accomplish the missing tasks. A few refinements were proposed but without assuring a final solution for the resulting dilemma (Rafferty, 2022).

A new formula started to arise following 1992—the temporary renting contract, involving new agreements with no long-term commitment. The owners’ duty was to ensure structural integrity, while tenants were responsible for all internal maintenance. The new formula was more logical regarding renting fees, but it caused continuous transformation in the social structure. Eventually, there arose two temporary legislative systems that are currently active regarding rented buildings: Decree 159/1992, which is dedicated to new rental contracts with temporary residence based on yearly contracts and in which fees are estimated upon agreement between owners and occupants; Decree 160/1992, which is dedicated to old rental contracts, where occupants’ renting periods are automatically renewed, and thus, the rental agreement does not have an end date. The rental fees in this case do not conform to the actual market (Smith, 1979). As established, most rented residential and commercial divisions in historic buildings in Lebanon have contracts that mostly date back to before 1992. Hence, most rents are fixed at a very low price, which discourages refurbishment initiatives by both owners and tenants.

3.2 Maintenance situation

The recent legislative adjustments have assigned more maintenance duties to tenants, especially in the case of new rentals (159/1992). Furthermore, interior works expenses for housing units should be afforded by occupants, as outlined in chapter 49/legislation 2014 for both cases. Exterior works or common building accommodations are subject to agreement between owners and occupants, respecting a specific ratio where an owner’s contribution should never exceed 5% of the annual income of rental fees. However, structural integrity is always a responsibility of building owners; this fact has led owners in most cases to neglect maintenance as it would emphasize their properties’ captivity to the extended old rental laws (160/1992) with the hope that their edifices would crumble, which would mean that they are then able to sell a blank territory. Owners are not interested in renewing building facilities due to the low income in all renting situations, while tenants have neither the will nor the means to achieve any restoration; they just contend with the least possible.

3.3 Historical building legislation

Lebanese legislation has not assigned any legislation regarding historical buildings or the urban conservation process. The main regulation is the outdated 1933 High Commissioner decision on antiquities (Ashkar, 2018). As a result, several historic buildings have experienced a regrettable fate—that of demolition and replacement by towering apartment blocks or temporary parking lots.

According to Mona Al-Hallak, an architect and activist who fought for years to preserve Beit Beirut, a 1995 study of Beirut’s heritage buildings demonstrated that Lebanon has no legislation designed to incentivize the preservation of historic buildings, leaving cash-strapped owners with few options but to sell them, leave them to rot, or seek demolition permits.

However, the traditional urban morphology represents small-sized units along with inheritance complications. This nature implies the necessity of legislative formulation in order to promote the safeguarding of built heritage. It is conceivable that a slight improvement was achieved due to decree 16353, issued in 2006, in which some guidelines are outlined in order to promote non-destructive uses of historical buildings and areas.

The first clause in the above-stated 1933 Lebanese Antiquities Protection Law No. 166 declares that any building constructed before 1700 is considered an antiquity, automatically registered in the General Inventory of Historic Monuments and protected from demolition and degradation. However, this law has a very narrow perspective in defining and classifying built heritage and in protecting the heritage urban fabric. As a result, based on the General Inventory of Historic Monuments, only 75 buildings out of a total of 500 buildings in this inventory are in Beirut. Furthermore, the field survey by the authors revealed that most of the built heritage in the capital city remains unprotected and subjected to various threats.

In October 2017, the Cabinet approved a draft law to protect Lebanon’s architectural heritage, forwarding it to parliament for discussion, but the law has yet to appear on the parliament’s agenda. It aims to appeal to owners, developers, and investors on the one hand and activists, urban planners, and architects on the other. Its pièce de resistance is a proposed mechanism allowing the transfer of development rights (Joana Hammour, Save Beirut’s Heritage).

The new law also incentivizes owners to take the initiative to register their houses as heritage properties, affording them 100 percent of the TDR proceeds if they do so rather than the 75 percent received if the state approaches them. Owners protested the bill in the following March, requesting that the government clarify its wording, include owners in the decision-making process, and take responsibility for preserving all heritage buildings (Kirsten O'Regan).

4 Case study selection

Generally, there is a lack of conservation legislation and implementation in developing countries, Lebanon being only one example (Al-Hasani, 2011, Naji Maher-Nasr-e-din 1991). Since this study focuses on analyzing the impact of occupation on the physical condition of historical dwellings under the existing official rental legislation, its scope and limitations are confined to a specific set of historical buildings in Tripoli, Lebanon.

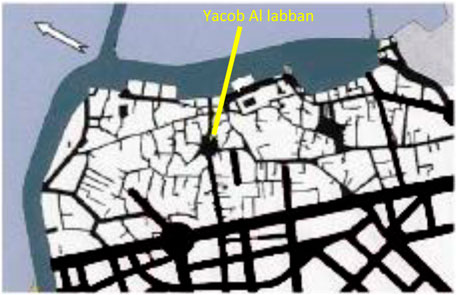

The Yacob Al Labban historical square was chosen as the research case study as it is located in the heart of the El-Mina district in Tripoli, which lies on a rich archaeological layer, with all local historical references locating the Phoenician ancient city beneath the current El-Mina (Lahoud, 2013). El-Mina’s population is basically formed of two communities: Muslims and Greek Orthodox (Figure 1). They almost entirely live in two agglomerations neighboring the Labban Square.

FIGURE 1. Aerial view showing Tripoli and old El-Mina labeling the two communities’ neighborhoods (source: https://www.google.com/maps/@34.441088,35.8205901,6590m/data=!3m1!1e3).

The urban fabric is essentially formed of historical buildings mixed with some scattered modern structures. The targeted area develops around a central square known as Labban Square. It is about 229 parcels, occupying an approximated area of 3 hectares. Modern history has witnessed a remarkable local prosperity marked by the presence of three cinemas during the 1970s. However, the post war socio-economic changes have left the district in a different state, mostly marked by building deterioration and social discrimination. Looking into the site’s components, the central square’s area is almost 2,500 m2, and there are two elements holding the most valuable identity.

In the square, there stands Saint George’s chapel, which holds the distinction of being the oldest recorded building, its construction dating back to 1735. A notable feature within the vicinity is a statue positioned at the center of the square serving as a memorial to Dr. Yacob Labban (Figure 2). Dr. Labban, a respected member of the Lebanese Christian community, earned great admiration for his philanthropic acts, offering solace to the less fortunate and assisting those in need. The square and the nearby street, known as the Christian souk, were named in honor of Dr. Labban, commemorating the enduring legacy (Figure 3) of a man who dedicated over six decades of his life to serving his community. It is always noticeable that some buildings always involve a sense of nostalgia for the local community as being witness to a missed period or opulence and social integrity (e.g., the cinemas and the Red Cross headquarters).

FIGURE 2. Some of the square’s architectural features (Saint George’s Orthodox church and the statue of Dr. Yacob Labban) taken from Labban Square (by author).

5 Field survey

The field survey was conducted to assess the physical condition of the historical dwellings surrounding Yacob Al Labban historical square in Tripoli, Lebanon. The researchers systematically inspected the exterior and interior of each dwelling, documenting their observations. Aspects such as architectural features, decay or damage, and maintenance practices were assessed. Consultations with local authorities and local inhabitants were sought. These investigations provided valuable data analysis and firsthand observations on the physical condition of the historical dwellings, serving as a crucial foundation for the subsequent analysis and discussion. Furthermore, the research utilized data analysis of the existing official municipal documents of the specific study area. The data found were to be used to determine the effect of occupation on the physical conditions of the dwellings under the different prevailing official legislations and to establish a link between these two latter factors.

5.1 Occupancy status survey

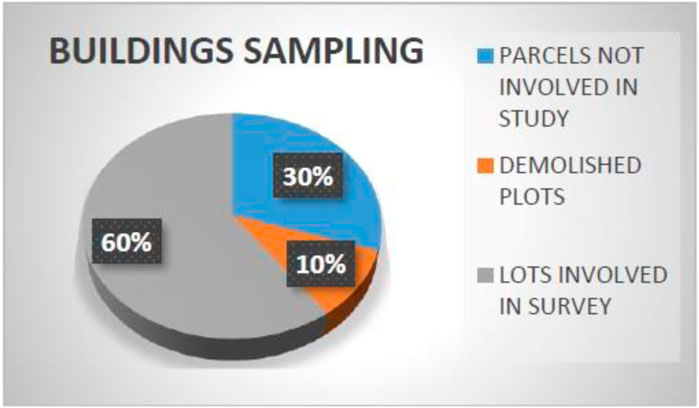

The legal status of occupancy was determined by referencing the official municipality tax documents. A survey was conducted on 83 parcels out of a total of 137 lots within the study area, encompassing approximately 60% of the overall real estate present in the neighborhoods (Figure 4). However, it should be noted that the municipality documents may not encompass all rental agreements, particularly those involving “illegal” arrangements managed by tenants. Additionally, certain commercial units may be subject to multiple rental agreements, starting with an official tenant and subsequently transferring the use of the built unit to a third party.

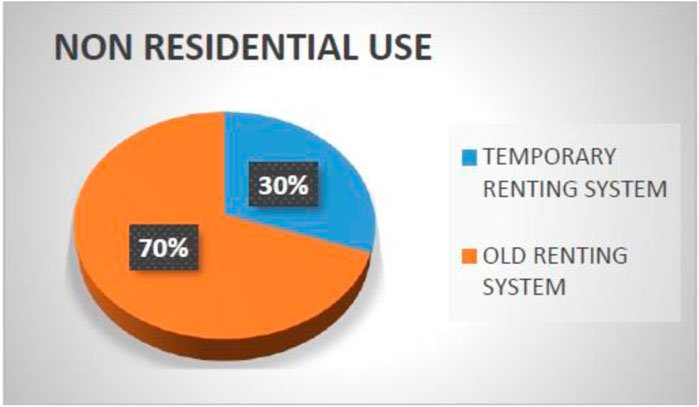

The presented data in Figures 5, 6 is measured from the sampled buildings as given by municipality official tax documents. The sample survey comprised 83 lots, consisting of 191 non-residential units and 229 residential units, based on the available official data (Figure 7). However, it is important to note that the local municipal archives do not have records for the remaining parcels for various reasons. This includes approximately 14 lots that have been demolished, exclusion of religious and municipal properties from the list, and the lack of documentation or restricted access to the rest of the plots due to administrative factors. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that certain rental cases may not be officially registered due to unique circumstances.

FIGURE 5. The survey results concerning non-residential use under the temporary renting system (30%) and old renting system (70%).

FIGURE 6. The survey results concerning residential use under the temporary renting system (28%) and old renting system (72%).

5.1.1 Non-residential use

Non-residential use in the surveyed area is primarily observed in ground floor shops, with some cases of upper floors being utilized as offices. It is noteworthy that 58 units are rented under the new rental legislation, while 133 units are governed by the old renting law, resulting in lower income for the property owners. According to the official documents, a minority of rented units generate an annual income slightly surpassing the minimum wage (675,000 L L per month), aligning with the interests of the owners.

5.1.2 Residential use

The residential units encompass both upper floors and ground floor levels in the case of inner alleys, totaling approximately 229 units, as documented by municipal officers. Among these, 63 units are subject to the new rental legislation, while 166 units adhere to the old renting law and its associated implications. Based on the owners’ preferences, official documents indicate that a small percentage of the rented units generate an annual income slightly exceeding 3,000,000 L L per year, which is approximately 50% of the minimum wage (675,000 L L per month).

It is evident that a significant portion, approximately 70%, of the entire built area is subject to rental agreements under the old system, with minimal fees. Among the property owners who rent out their properties, a substantial number, accounting for 70% of households, are governed by the old rent law. Additionally, the study confirmed the presence of numerous abandoned buildings in the area.

5.1.3 Monetary implications

Municipal tax files show the official renting fees for each unit; surprisingly, actual fees are out of the admissible range even in the case of the temporary rental system. This fact may parallel the morphology of the buildings or the social environment, which may both be playing a negative role concerning building economic validation. On the other hand, the low renting fees are directly connected to the lack of maintenance in all renting types.

Since local historical preservation laws have pushed municipal departments to adopt new policies regarding landmarks owned by the government, this had led to the stemming of the loss by demolition or irrevocable alteration of historic resources and their landscape settings. Additionally, the municipalities have established incentive provisions for the rehabilitation or adaptive reuse of historical structures.

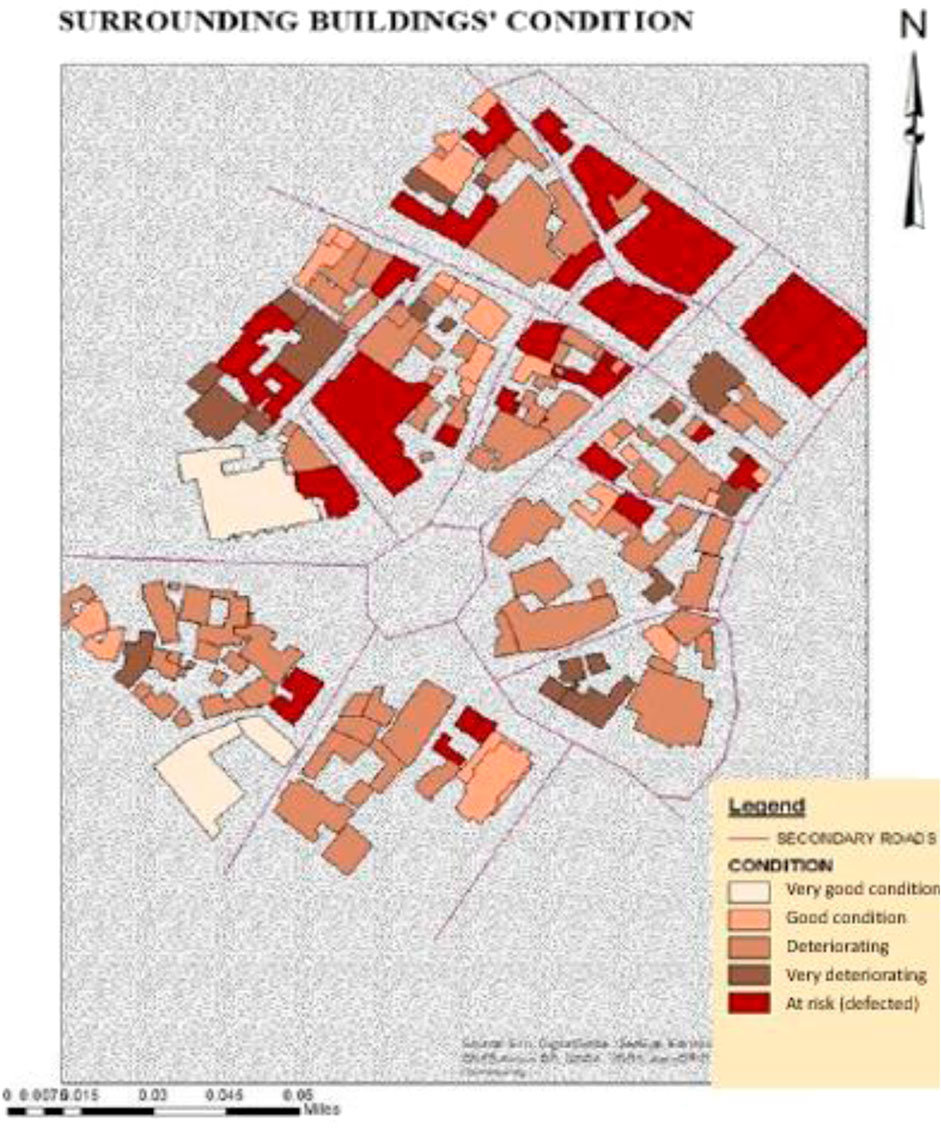

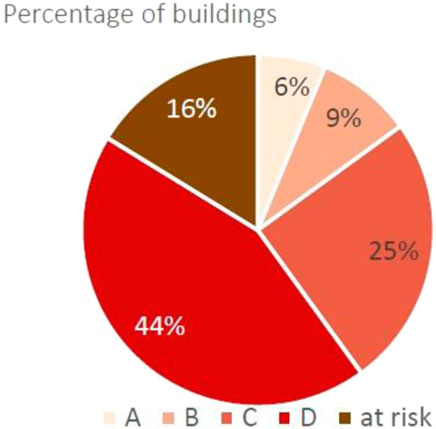

5.2 Buildings physical state survey

As shown in Figures 8–12, the survey conducted on the physical state of the buildings resulted in their classification into five categories: very good physical condition, good physical condition, deteriorating, very deteriorating, and at risk. In the current context of this area, most of the buildings were observed to be in a deteriorating physical condition, with many of them concentrated around the square. These buildings were originally designated for residential use and have undergone alterations and renovations. On the other hand, buildings in good physical condition have mostly been restored and preserved. However, those in deteriorating and very deteriorating conditions are either undergoing alterations or have been left unused. The accompanying map provides a basic overview of the current scenario regarding the condition of the buildings within the study area.

FIGURE 9. Degrees of deterioration as taken from the site survey (A): 6% very good, (B) 9% good condition, (C) 25% deteriorating, (D) 44% very deteriorating, and 16% at high risk).

FIGURE 11. A chart showing the renting state (blue (7%) represents the new renting system, and brown (93%) represents the old renting system).

It is evident that the entire urban fabric in the studied area is undergoing varying degrees of deterioration, with different rates observed for each type of building. Notably, the northern part of the area appears to have a higher prevalence of major defects compared to other regions where the majority of buildings are in good condition. However, a smaller percentage of buildings are classified as being in an at-risk condition. Deterioration poses a significant challenge to urban spaces, leading to imbalances and neglect of residential structures. This issue impacts both the security of occupants and the overall quality of the living environment (Habib, Farah, and Peimani, Nastaran, and Daroudi, Mohammad, 2013).

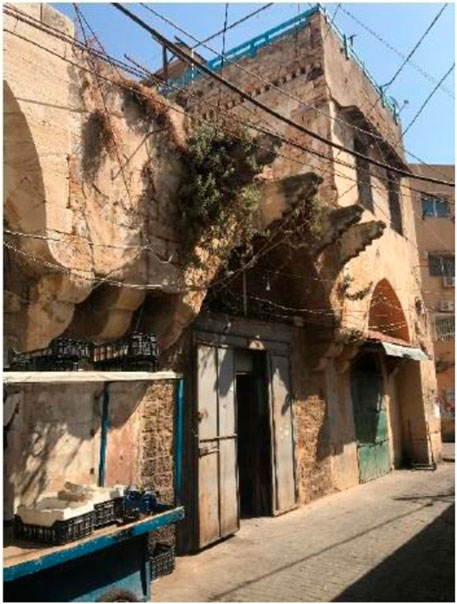

5.3 Buildings with major defects

Among the surveyed buildings, it is noticeable that some cases represent major defects concerning materials or even structural integrity. Such defects include cracks and damages on the walls and beams and issues with the fire systems and waterproofing. These significant deficiencies have the potential to not only render the building unusable for its intended purpose but also pose a severe threat of collapse or destruction to all or part of the structure. It is essential to address these defects promptly to ensure the safety and usability of the buildings and mitigate potential risks to occupants and surrounding areas.

A subset of approximately 27 buildings within the surveyed area exhibits the most severe defects. The majority of these buildings (93%) are rented under the old system. In order to restore these structures to a habitable state, renovations or reconstructions are crucial. However, it is equally important to ensure that the historical aspects and architectural heritage of these buildings are carefully preserved during the restoration process. This dual approach of addressing both structural deficiencies and historical significance will contribute to the revitalization and sustainable use of these historical dwellings.

In addition to the aforementioned group, there are also a few buildings within the studied area that remain unused despite being available for rent. The analysis of the chart reveals that all the examined buildings exhibited defects. Notably, 93% of the sampled buildings operated under the old renting system, while the remaining 7% followed the new renting system. These findings strongly suggest that the old renting system has significantly contributed to the prevalence of building defects, while the new system appears to be more sustainable. Nevertheless, these results emphasize the need for continuous improvement in the renting systems to enhance performance, ensure safety, and address the existing challenges associated with the current systems. Further reforms and measures are necessary to promote better functioning, minimize defects, and create more favorable conditions for both landlords and tenants.

6 Results and discussion

The research findings reveal several significant aspects related to the link between dwellings’ deterioration and rental legislation in Lebanon. In the studied area of Tripoli, a considerable percentage of inhabitants rely on rental arrangements, with 93 percent following the old rental system characterized by minimal fees for affordability. This affordability factor poses a challenge to refurbishment initiatives by both owners and tenants as the low rental prices discourage investment in maintenance and improvement efforts. Consequently, inadequate or poorly enforced rental legislation contributes to landlords neglecting the necessary upkeep and repair of dwellings, ultimately leading to their deterioration over time.

This study also highlights the correlation between the physical condition of historical buildings and official local authorities’ legislation in Lebanon. The analysis reveals that these buildings have suffered from a prolonged period of inadequate conservation and maintenance practices. This observation underscores the need for comprehensive legislation specifically targeting historical buildings and urban conservation in Lebanon to prevent further deterioration. The absence of dedicated measures in this regard has resulted in the demolition and replacement of historic structures, aligning with the findings of Ashkar’s study in 2018.

The findings are consistent with previous research studies by Rafferty (2022) and Kayal and Atiyeh (2001), which emphasize the challenges arising from the continuous transformation of rental legislation in Lebanon. The shift from long-term agreements to temporary contracts since 1992 has not only affected social structures but has also discouraged owners and tenants from investing in refurbishment initiatives.

Furthermore, the analysis of the surveyed buildings in the Tripoli area reveals significant defects in terms of materials, architectural elements, and structural integrity. These defects include cracks, damages to walls and beams, and issues with fire systems and waterproofing. The presence of these defects highlights the urgent need for maintenance and repair interventions to prevent further deterioration and ensure the structural stability and safety of the buildings.

In conclusion, the research findings demonstrate the adverse effects of inadequate rental legislation on dwellings’ deterioration in Lebanon. The affordability-driven rental agreements hinder refurbishment efforts by both owners and tenants, while the absence of specific legislation for historical buildings exacerbates their physical decay. The results underscore the importance of robust and comprehensive rental legislation to protect the quality and livability of rental properties. Additionally, targeted measures for preserving historical buildings and urban conservation are essential to prevent further deterioration and promote the long-term sustainability of Lebanon’s architectural heritage.

7 Conclusion

This article investigates the link between the physical condition of built heritage and official local authorities’ legislation in Lebanon. The analyses prove that the manipulations of the regulatory structures for building development in Lebanon have exhaustively inspired a thorough circulation of capital, enabling private actors to lead in the planning of the city. Private capital and its demands have overthrown other priorities formerly protected by law, particularly those related to the common good. The accordance between owners and tenants has always been controversial due to the interference of duties and needs. It is obvious that the local old rental system is one of the catalysts for buildings deterioration; the related impact is not totally clear due to the interfering agents at the social and economic levels. In the case of historic buildings, there are some additional maintenance requirements along with special restrictions regarding function. It is a missed link, and new rental legislation is highly recommended to fill this gap.

This study has demonstrated that cooperative efforts among private and public stakeholders can play a vital role in the development of Lebanese heritage. In Lebanon, the approach to the “legal” has been devoid of the social, and the law has been reduced to the effects the political class has on the legislation process. Strategies for establishing a new legislative framework that is focused on protecting Lebanese cultural heritage, especially in the city of Tripoli, and ensuring sustainable adaptation planning are highlighted. Given that private and public stakeholders have had a major hand in the heritage development of the area under study, a recommendation of this research paper to these stakeholders is to work together and be a key catalyst for urban heritage conservation.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I extend my heartfelt appreciation to Architect Hazem Aysh - Engineering Coordinator at Islamic Awqaf of Tripoli, Lebanon - for his invaluable assistance in collecting essential data for this research paper. Hazem’s expertise and support significantly enriched the paper’s content. His dedicated contribution played a pivotal role in the successful completion of this research. Thank you, Eng. Hazem Aych, for your crucial role and collaboration.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afify, A. (2014). Sustainable improvement and management for deteriorated urban area in developing countries. Mandaluyong, Philippines: Asian Development Bank.

Al-hagla, K. S. (2010). Sustainable urban development in historical areas using the tourist trail approach: A case study of the cultural heritage and urban development (chud) project in saida, Lebanon. Cities 27 (4), 234–248. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.03.002

Al-Harithy, H. (2010). “The politics of identity reconstruction in post-war reconstruction,” in Lessons in post-war reconstruction. Editor S. Sassen (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge), 85–113.

Al-Hasani, N. (2011). Conservation of architecture and settlements in Lebanon: Two case studies. Cambridge, MA, USA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Amiot, C. E., Dela Sablonniere, R., Terry, D. J., and Smith, J. R. (2007). Integration of social identities in the self: Toward a cognitive-development model. Personality Soc. Psychol. Rev. 11 (4), 364–388. doi:10.1177/1088868307304090

Ashkar, H. (2018). The role of laws and regulations in shaping gentrification: The view from Beirut. City 22 (3), 341–357. doi:10.1080/13604813.2018.1484641

Brown, A., and Wilson, J. (2019). The impact of inheritance rules on residential property maintenance. J. Prop. Res. 36 (3), 272–288. doi:10.1080/09599916.2018.1554308

Díaz, S., Demissew, S., Carabias, J., Joly, C., Lonsdale, M., Ash, N., and Zlatanova, D. (2015). The IPBES conceptual framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 14, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002

El-Bastawissi, I., Raslan, R., Mohsen, H., and Zeayter, H. (2022). Conservation of Beirut’s urban heritage values through the historic urban landscape approach. Urban Plan. 7 (1), 63–73. doi:10.17645/up.v7i1.4762

Elnabawi, M. H., Hamza, N., and Sultan, M. (2022). “Beyond the gates: Extending the markets of fatimid cairo to Al-khayamiya bazaar’’ in,” in Architecture and urban transformation of historical markets cases from the Middle East and north africa (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge). doi:10.4324/9781003143208

Jin, S., Ye, H., Shaobin, W., and Sedki, A. (2022). Preservation and utilisation of historic buildings in old district of guangzhou from the perspective of space syntax. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 7. doi:10.2478/amns.2021.2.00208

Lahoud, A. (2013). Architecture, the city and its scale: Oscar Niemeyer in Tripoli, Lebanon. J. Archit. 18 (6), 809–834.

Peppercorn, I. G., and Taffin, C. (2013). Rental housing: Lessons from international experience and policies for emerging markets. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank Publications.

Rafferty, M. (2022). Relational urbanisation, resilience, revolution: Beirut as a relational city? Urban Plan. 7 (1), 183–192. doi:10.17645/up.v7i1.4798

Sadi, S., Aksah, H., and Ismail, E. D. (2013). Heritage conservation and regeneration of historic areas in Islamic cities: Case study of Tripoli and Tyre. Procedia-Social Behav. Sci. 85, 394–404.doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.03.002

Salam, A. (1998). “The role of government in shaping the built environment,” in Projecting Beirut: Episodes in the construction and reconstruction of a modern city. Editors P. G. Rowe, and H. Sarkis (Munich, Germany: Prestel), 122–133.

Sandes, C. A. (2013). “Urban cultural heritage and armed conflict: The case of beirut central district,” in Cultural heritage in the crosshairs (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill), 287–313.

Scerri, M., Edwards, D., and Foley, C. (2016). “The value of architecture to tourism,” in Proceedings of 26th Annual CAUTHE Conference, Sydney, NSW, Australia, February 2016, 1–21.

Sitte, C. (1889). “City planning according to artistic principles,” in Camillo Sitte: The birth of modern city planning (Antonio, TX, USA: Urban Design Group), 129–332.

Smith, N. (1979). Toward a theory of gentrification: A back to the city movement by capital, not people. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 45 (4), 538–548. doi:10.2307/600321

Smith, R., and Johnson, L. (2018). Property division and conflict resolution in inheritance law. Eur. J. Law Econ. 46 (1), 135–155. doi:10.1007/s10657-018-9604-5

Keywords: historical dwellings, conservation, renting legislations, building physical condition, historical urban spaces

Citation: Sedki A (2023) Evaluating the influence of old and new rental systems on the physical condition of historic mixed-use buildings: a case study of Lebanon. Front. Built Environ. 9:1190374. doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2023.1190374

Received: 20 March 2023; Accepted: 06 July 2023;

Published: 26 September 2023.

Edited by:

Hamdy Mohamed, Université de Sherbrooke, CanadaReviewed by:

Yasser Megahed, Cardiff University, United KingdomTareq Abuimara, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2023 Sedki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Sedki, ali.ali@asu.edu.bh

Ali Sedki

Ali Sedki